Motivation…

Working with drum students, I find myself having to (repeatedly) explain to kids and adults how to think of their drumming as a concerted effort of separate motions.

Controlling sticks with hand muscles is one thing, but learning to control the kick drum pedal(s) is another challenge altogether.

It is often clumsy to explain how to get control, let alone finesse, from their feet through the pedals, so I often have to touch, handle, or even high-jack their moving legs and feet to show them what to coordinate certain kick-pedal motions effectively.

Searching for some basic overview of “drumming muscles” reference material to assign them, I found this very anatomically-informed video by SimplySnare…

…but I wanted to compile some deeper notes to illustrate the ergonomics of some more advanced techniques.

Let’s start with the Stick.

Before we get into the problem of the feet and the confounds of the pedal, let’s get a grip (literally) with the heritage of ergonomic drumming in our hands.

Review of Moeller’s THREE stroke motions

The name “Moeller” and “Moeller technique” is synonymous in the drummer world with economy-of-motion and stick control. Formalized by Sandford Moeller (1886-1960), he did not invent the system, so much as formalize a language for stick control by observing the play of the great drummer of this time.

The system has been (re)popularized and (re) contextualized by technique-savvy drummer/teachers across the subsequent generations, including Jim Chapman, Freddie Gruber, and more recently Jojo Mayer.

Moeller’s technique facilitates relaxed stick control for fast play by defining 3 strokes (for either hand, with discrete control of using finger-squeeze and/or wrist-motion to propel the stick.

- Down strokes for accents. Wrist comes down

- Tap strokes for non-accents. Hand stays down, stick will “flys back” into the (loosened) grip of the hand to recoil without the wrist. Successive stroke is propelled (mostly) by finger grip.

- Up strokes for non-accents that prepare for new accents. Wrist brings hand up.

The gist of the technique/system can be explained and visualized and explored with one- and two-hand applications in a Jim Chapman diagram.

The fundamental Moeller motions are initially trained in each hand alone. For the sticking of two-handed figures, we can see the intertwining of each hand’s strokes.

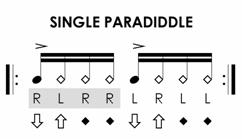

For example, in a simple para-diddle (with accents on the downbeats 1 and 2)…

…we see each hand’s role in the Para-diddle executing the same sequence…

- Down

- tap

- tap

- Up

…independently, just a half-cycle out of phase.

Let’s stick to single-limb exertion from her out.

Relaxed flexion: from muscle suspension to muscle flow (learning deep from hard and slow).

The traditional Moeller fundamentals are great, even essential, for learning to “relax into playing fast,” but I’ve always felt some ambiguity to “playing relaxed”. Obviously, muscles cannot remain slack and still play strike drums; our muscles must flex. Hence, it’s a more accurate ideal that we remain more “calm” and “in control” if we train to flex them ONLY and EXACTLY what and when is necessary.

I didn’t appreciate the principals deeply until I struggled with the opposite challenge…. learning to playing SLOW..

Up until 2010, I had played in mostly “rock” and “punk” bands, maintaining moderate tension while playing medium to frantic drumbeats.

In 2010, when joined nerd-doom band WormRider, I had to quickly learn to maintain sparse, caveman patterns at glacial tempos. It proved more exhausting than “rock and roll,” because I was holding tension from shoulders to fingers those pauses (often many seconds) between slams. After waking up sore after several rehearsals and shows, something clicked; instead of suspending my muscles in some imitation of “slow motion drumming,” I had to play more fluid motions, with more wind-up and follow-through, and let myself relax in those moments.

early show playing with WormRider 2010. learning to relax not just between songs, but in between strikes…Head up, shoulders and elbows down, sticks forward.

As I learned to “zone in” to playing hard and slow, working to remain fluid, I became more sensitive to feel when entire chains of muscles flex and relax. I soon could handle dynamics and even ghost notes among the “sludgy pummeling.” With an renewed (if inverted) curiosity and practice for exploring traditional Moeller principles, I consider how the muscles, motion, and tension in my fingers and wrists are not only connected to each other, but to larger support structures of the elbow/shoulder/etc.

Learning a “state-dependent model” of FOUR stroke-states

As I learned to play fluidly from seeking economy-of-motion from pushing both my fast and slow, I became sensitized beyond controlling my muscles control accents for hard (“H“) and soft (“s“) strokes. We also must control our muscles, grip, and stick not just for the present stroke, but also to prepare for what intensity of stroke comes next.

This is evident in both fast and slow extremes. On the fast side, for example, as a double-stroke roll (“RRLLRRLL…”) speeds up, the second bounce in each hand is almost entirely motivated by grip-tension-ed rebound, where the wrists are only activating for the first of each par (“RrLlRrLl…” as “HsHsHsHs…”). On the slow end, as I deflated the tempos on patters that mixed syncopated ghost notes with full-swing back-beats, slowing them to slow down below 50 BPM, my hands would stay UP or DOWN for to anticipate accents or ghost-notes on their own.

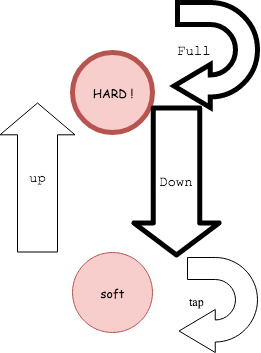

Thus I came to understand a muscle-future state approach to stick/hand control can define FOUR stroke types.

- FULL ( H->H ) : start high to hit Hard, full recovery to prepare for another Hard.

- DOWN ( H->s ) : start high, hit Hard, end low to subsequent soft stroke(s).

- TAP ( s->s ) :start low, hit soft, stay low

- UP ( s->H ): start low, hit soft, pull rebound up for future hard hits.

We can summarize these “future-state-dependent” categories into a accent-stroke flow-chart. If we orient the flowchart top-to bottom, we see states reflect the stick-height that is essential to accent control.

Feet?

Putting this mettle to the pedal ?

Let’s see how these ideas translate to a drummer’s feet, which tend to move around space less, but may be more prone to syncopation (to lock into the pulse and phrasing of the music).

Parts and Mechanics:

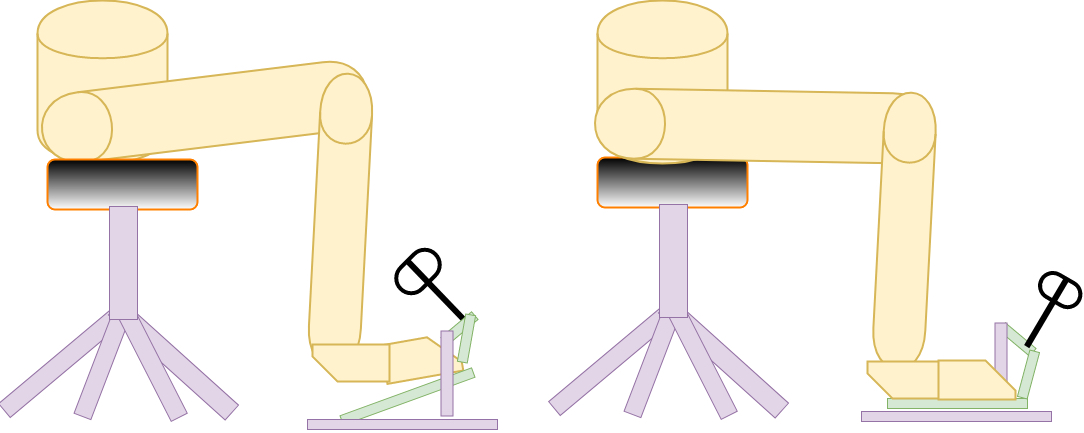

The design of a pedal is simple enough; transferring foot motion into striking energy through specific mechanics.

- a drummer steps on a foot board, which is anchored at a hinge at the heel

- this motion pulls at the pedal drive, to convert the moving leverage to rotation of the beater.

- This drive may be a direct-drive joint, or pull a chain (or strap) around a cam, and design options here give a pedal its unique “feel”.

- the beater strikes the drum/trigger/etc.

- a spring (or other tension system) is strained under motion, and upon release, restores the pedal to “ready” position.

Seems easy enough, the retail market seems to hold consistent demand for all combinations of the various design options. Where we may consider our choice in drum-shell colors to a be purely aesthetic, or our choice ins cymbal flavoring to be one of “sonic palate,” the kick pedal is a hugely ergonomic commitment.

Just as easily as my students may prefer the “feel” of one pedal design to another when they are just starting out, they may find it helpful or frustrating to switch designs as their technique and ambition grows. After playing for two decades, I still find there is no “perfect” pedal for me, as I tend to adopt different playing advantages for each.

Without diving into the wormhole of pedal design options, let’s stick to the ergonomics of how a drummers muscles can move to drive a pedal effectively, and what (tends to) happen when certain motions meet practical limits.

Heel Up or Down ?

Whether drummers are just learning how to use their first pedal, work-shopping their technique to play faster, or window-shopping for more efficient hardware, we often come to the same question:

“…do you play ‘heel-up‘ or ‘heel down‘ ?…”

What doe this mean ? It defines how we “situate” our self into our pedals, and which muscles we use to PUSH (“kick”) and PULL (“recover”) the foot pedals.

In short:

- Heel-UP players connect to pedal at ball-of-foot, PUSH-ing pedal with combination(s) of thigh/knee muscles dropping and ankle swiveling, and PULL-back nter a caption

- Heel DOWN players anchor heel on back of pedal plate, push with ankle muscles, and recover with shin muscles.

The physiology is topic is introduced and illustrated in excellent depth at this Physiology 101 article at Drum! magazine (however, they may have their diagrams backwards…).

Since a “heel up” player can use their calf muscle (to flex toe downward) AND/OR the thigh muscle (drop stiff-foot onto pedal), we see that different stroke motions combine muscle in different ways. Subsequent movement-analysis in this article will be focused (biased) by my (limited) mastery of playing “heel up.”

In my experience, I’ve found heel-UP to afford (me) much more power and finesse. Conversely, I’ve found heel DOWN to be weaker and exhausting, as it has greater reliance on fewer, smaller muscles without “throwing weight around”.

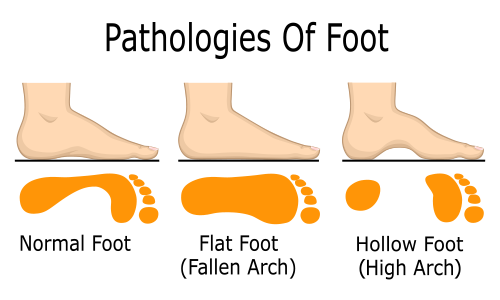

Oddly enough, however, I’ve seen a handful of drummers who can sustain impressively fast double-bass rolls with their feet, and when I’ve asked, they all mentioned they were flat-footed (with collapsed arches). This is just my observation; I haven’t done official research yet.

views of foot-arch types and profile.

LEFT: traditional (arched)

MID: “flat-footed” feet (colapsed arch).

RIGHT:BOTTOM:

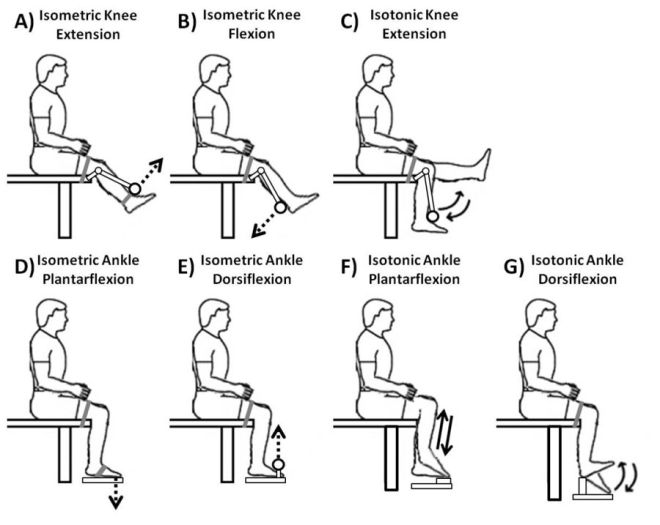

Inventory of our “kick motions and “kicking muscles”

If we’re going to talk economy-of-motion, we should

- first consider how the leg (tends to) move on a pedal,

- then consider the roles and names of the different muscles moving independently

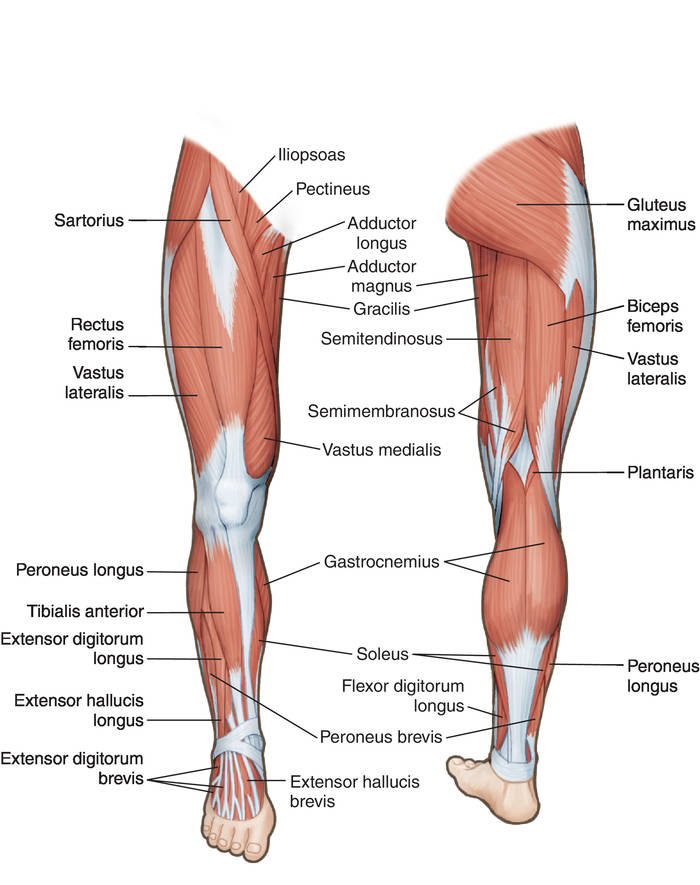

From Medical Dictionary, we see both the flexors and extensors that would motivate a leg to kick and pedal from a seated posture.

From the (dense) chart above, let’s make some connections between the (plain English) “names” of the motions of interest, the direction of muscle movement (flex or extend) and name the (primary) muscles involved.

…knees…

- “leg down” Thigh- and Knee-extension : the top thigh (Rectus femoris,…) and some groin muscles (Adductor magnus) contract to extend leg straighter into the pedal.

- “leg up” Thigh- Knee-flexion: the under-thigh muscles (Biceps femoris, Seminteninosus, …) and front pelvic muscles (Pectineus, iliopsoas) muscles contract to flex the leg into a more angles, pulling off the pedal.

…and toes…

- “toe down” Plantarflexion the strong calf muscles ( Gastrocnemius, Flexor digitorium…) contract to flex the down straighter “Z shape”

- “toe up” Dorsiflexion : the generally-weak shin and arch muscles (Tibialis anterior, Extensors hallucis…) contract to extend the toe upward

If you, at this point, interested in how differently these muscles heat up and exhaust during sustained play, check out this article on “Qualitative Evaluation of Physical Effort in Bass Drum Pedal Drive by Thermography” from Science and Technology.

For my purposes, let’s try to isolate distinct movements on the pedal.

Just 4 strokes ?

The classic Moeller (and my “state-dependent”) model(s) of hand-drumming motion are based on supporting accents by stick height.

If we look at state- and stroke-types for a single foot, working a pedal, within heel-UP technique, I tend to find and teach (others or myself) the following ergonomic distinctions…

- kick the pedal (mostly) with our calf,

- lift and drop our thigh (mostly) for accents, with preference for downbeat

- employ our ankle/toe muscles only to control rebound for quick double-strokes (or more) strokes.

…which allows us to translate the elbow/wrist/finger actions for the stick to the knee/ankle/toe articulations for the kick pedal as accordingly:

- a FULL kick

- heel starts up, ends up.

- leg-down muscles effectively drop weight below knee onto pedal, tension-ing pedal-spring

- toe-down muscle often remain flexed so that “leg-weight” transfers power to push pedal plate down.

- leg-up muscles (should) pull up knee

- pedal spring relaxes to lift plate, maintaining contact with (usually ball-of) foot

- a DOWN kick

- heel starts up, ends down

- leg down muscled push knee down,

- toe muscles relax to let foot land heel-down on plate.

- toe muscles may flex to maintain tension on pedal spring, for a “buried beater” technique to muffle drum response.

- a TAP kick

- heel starts down, ends down,

- toe-down calf muscles flex ( in relatively limited range of motion).

- calf may draw foot backward on pedal plate for greater leverage from short stroke-space with an already-stretched spring

- an UP kick

- heel starts down, ends up,

- leg-up muscles lift knee (for subsequent FULL or DOWN accents)

- pedal spring relaxes, plate follows foot.

- toe-down muscles may slide toe forward

However, given the complexity of transfer of energy from a (seated) leg through the leverage of a spring-loaded pedal, drummers do not often learn these as robotic, discrete motions. Instead, student thrive by learning “compound” motion (or flows) needed to tackled the challenges of double- and triple-strokes as they learn more syncopated kick work.

Application of kick-pedal stroke types … in “D”

Enough theory, let’s see some proof and example.

For illustration, let’s apply these motion/analytics to the the “D-Beat,” a syncopated drum pattern ubiquitous to hardcore punk music, and regularly played fast and loud; a natural adaption for economy of motion.

First, let’s hear the pattern and it’s origins.

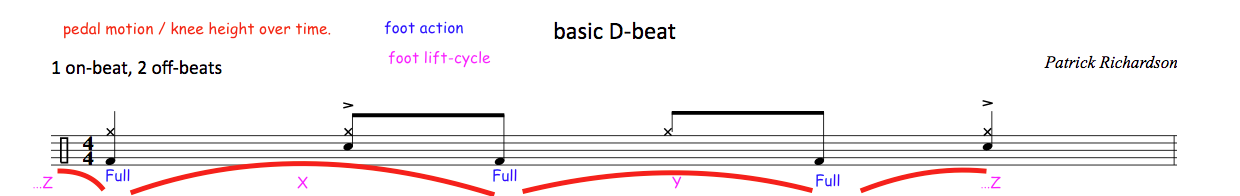

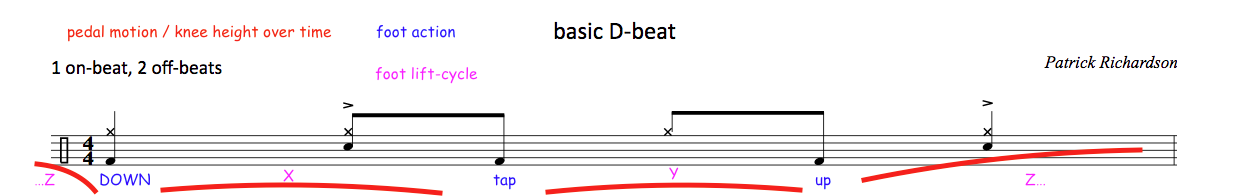

And look a the notation.

If you watch the knee on Brian Roe in the demo video above, you see all three kicks in a measure…

- the downbeat of 1

- the upbeat/”and” of 2

- the upbeat/”and” of 3

…and notice Brian’s leg moving the same manner with the same sweep of the knee. According to my nomenclature above, he’s playing FULL strokes for all (at that tempo). If we tracked his leg elevation across the time-line (of the notation), we can see that this “FULL (X), FULL (Y), FULL (Z)” pattern is broken up only by it’s offset timing,where the three lifts…

- X: “1” into “2’s AND”

- Y: “2’s AND” into “3’s AND”

- Z: “3’s AND” into the “1”

requires the middle leg-cycle (from “2’s AND” to “3’s AND”) to be quicker than the other two ( motion (into “1”) to be quicker than the following two.

When I try to play the D-beat faster (above 300 BPM as written), “choreography” of my leg changes. I find myself playing more with my foot (“tap”s) and only move my knee to lift and drop an accent on the “1”. Thus, when pushed, (my control of) the D-beat gets reduced/smoothed to a single knee-motion-per-bar if you play a DOWN (X), TAP (Y), UP (Z) pattern.

Moreover, I’ve found that (my choices in) foot motion is NOT solely dictated by usage of “knee drops” for accents.

“Stepping down” on “downbeats”

As soon as I discovered “my D-beat macro-motion”, I started scrutinizing my playing more in any way I could.

- I talked to students about their playing.

- I asked students to lock their eyes (or even keep a hand) on my knee and/or ankle.

- I watched video of myself playing at normally, as well as pushing the extremes of fast (and slow) playing.

- I spoke to experts in the field of dance, or movement analysis, such as fellow Oberlin alumni Loren Groenenedaal, who specializes in both dance and Laban movement-analysis.

The more carefully I looked, the more I saw another meta-motion evident (in me).

I tend to remain more relaxed if I only only have DOWN or FULL steps (knee drops) on downbeats, and use my foot for offbeats… whether they come after or before such a worthy downbeat.

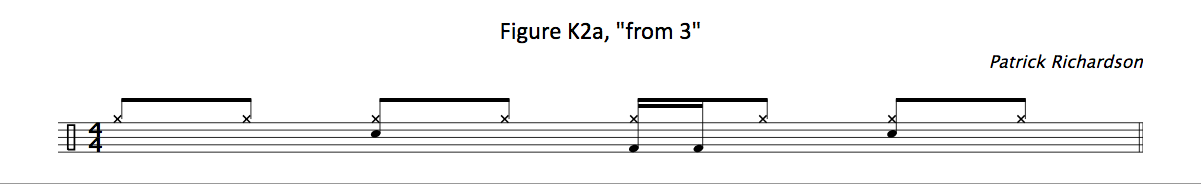

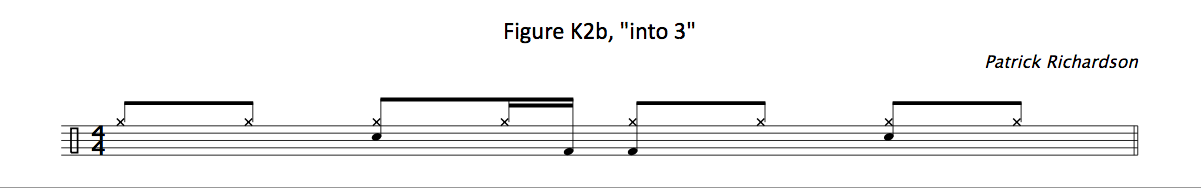

Consider the footwork of the following examples that require a “double-stroke” for two kicks (K2) from the same pedal.

…I play examples K2a and K2b differently, BECAUSE I tend to instinctively drop my knee on downbeats. Thus.

- when I play 2 (or 3) kicks that start on, and flow from a downbeat (such as K2a), I play a DOWN kick and play TAP(s) to follow.

- when I play 2 (or 3) kicks that anticipate, end on, ad flow into a downbeat: I found I use my foot/ankle muscles wile my let is raised (or rising).

I discovered a “HIGH” or “OFF” stroke with my foot, playing non-accents with my knee remaining high(er).

Heel-up non-accent makes FIVE foot-strokes !

So, at least in my technique and my analysis of it, I find a state-dependent system that captures (my) five distinct types of kick-pedal strokes.

- FULL – heel starts high, foot stays stiff, kick motivated by “drop” of knee-weight, heel ends high

- DOWN – heel starts high, foot relaxes/absorbs as knee drops to push pedal, heel ends low.

- LOW (TAP)- heel starts low, ankle and toe play non-accent, heel stays low.

- UP (OUT) – heel starts low, ankle & tow play play stroke that kicks pedal while propelling heel up to lift knee.

- HIGH (OFF) – heel starts up, pedal kicked by forward flexing toe/thigh, heel stays up. Mostly only used to anticipate a FULL or DOWN…

Left Hanging HIGH

I should stop here for several reasons.

First, I feel I’ve unpacked enough new/meta ideas for one read.

Second, I realize I need to perform and film examples before I can speculate and report further.

Third, and most importantly, I’d like to hear from other others (drummers, movement experts, robotics engineers, etc) before I proceed. Please let me know what you think in the comments below.

Cheers for now !

This explanation is awesome,✌️

Thanks G !

If you’re interested in getting into detailed consultations, I ovver lessons in-person (Philadelphia area) and remote (anywhere in world). Cheers !